Kerikeri, Bay of Islands

This was a new position and the first time that the department or National Parks and Reserves had been represented by a physical presence in the Bay of Islands. Hitherto, the Reserves Ranger Whangarei had been responsible for the many scattered reserves, whilst to the North, the Whangaroa area was administered from Kaitaia.

I suspect that my apprenticeship at North Head contributed to the selection and I was later told that it was felt that my experience in East Africa would enable me to better deal with the many former colonials settled in Kerikeri and the North. I found that there were some twenty-five ex-Kenya families in Kerikeri alone, some of whom I knew, indeed one family had made holiday use of my house on the beach at Kilifi, 40 miles north of Mombasa. Ironically, I have no recollection that during my fifteen years in the position the former colonials caused me any problem, rather it was the locals, those who had been resident in Kerikeri for many years, with whom I was to cross swords!

For some years before my appointment, the Society for the Preservation of the Kerikeri Stone Store Area (SPKSSA) had been fighting to stop a residential subdivision on the ridge adjacent to Kororipo Pa and overlooking the Basin. A Mr Veale had started work by felling a stand of mature eucalypts, doing earthworks and had installed road kerbing and storm water drainage before anyone took action. The society protested, called a public meeting and Mr Veale was asked to stop work. He declined and the society then approached the Crown asking for intervention and purchase of the land for addition to the Kororipo Pa Historic Reserve. The Crown demurred and the society started negotiations directly with Veale who agreed to sell the land to the society for a quarter million dollars. At least two of the principle members of the society mortgaged their own properties to raise funds and various fundraising activities were entrained including a scheme to informally sell nominal one foot square pieces of the property nationally and internationally. An agreement was reached with Veale but whenever payments slowed, he would again take to the land with his bulldozer.

Just before my arrival the Crown solved the impasse by buying the property from Veale and an additional five acres on the North side of the bridge from Mrs Pat Sinel, who retained life tenancy of an area about her house on the banks of the Kerikeri River. Things then settled down, but the society resolved to remain in existence and maintain a watching brief.

This was the position when I and my family arrived in Kerikeri on 15 February 1975 and moved into a rented house on a cliff at Skudders Beach with views down the Kerikeri Inlet all the way to Cape Brett in the distance.

I recollect that a few days after our arrival I had a telephone call, on the party line, from a Mrs Pickmere representing SPKSSA, asking what I proposed to do about the infestation of gorse and other weeds on the former Sinel property. I was flabbergasted! I didn’t know Mrs Pickmere, although later I came to know her well and so, as politely as possible, I told her that having only just arrived in Kerikeri, I was still unpacking and hadn’t yet had an opportunity to see the reserves, but hoped to do so within the next few days. This was portent of things to come.

In 1975, Kerikeri and district boasted around 1300 homes, a reputation for citrus fruit, an incipient kiwi fruit industry and a growing group of arts and crafts people. An annual piano competition had become a national event, the arts centre brought top shows to the town, and the Cathay was as much a social centre as a cinema.

Soon after I arrived, the reserves ranger Whangarei, Len McConnell, visited and we did a tour of some of the reserves that would fall within my district and I started to compile records. Clearly I would need several visits by Len to locate the various reserves and start to acquire maps, ascertain areas, and examine fencing and other issues.

In the Kerikeri Basin the Crown had control of the Kororipo Pa Historic Reserve and the adjacent Veale property, together with the five acres recently acquired from Pat Sinel, Possibly 15 acres in all, but mostly in an unkempt condition where gorse, tobacco weed, and gum trees, and other exotics flourished.

The owner of the house in which we were living at Skudders Beach turned out to be a shepherd on a Lands and Survey development block at Rangitane, just out of town, and through him I arranged to borrow a tractor and rotary slasher. With Mrs Pickmere’s query in mind I drove out to Rangitane one morning, picked up the tractor and returned intending to attack the gorse on the Sinel land. The land was roughly fenced and Len McConnell had arranged for a helpful local to graze a few sheep to help keep the growth down, I drove into the paddock, lowered the mower and entered the worst area of gorse only to be stopped in my tracks by a loud scraping sound that stalled the tractor. Inspection revealed that I had picked up the relics of an old fence that had been lying invisible beneath the gorse, with the No.8 wire well and truly wound around the shaft and blades of the mower. Much head scratching, I had no tools, knew no one, and was effectively stopped before I could start! I went to the service station, the government fuel contractor, and managed to borrow a pair of bolt croppers and some pliers and spent the rest of the morning untangling and removing the wire, What’s that old saying, “Look before you leap” — most apt!

By this time I had acquired a small chainsaw and set about removing some of the larger tobacco weed near the Sinel house. I didn’t like chainsaws and was extra cautious in using it. I took to one large old tobacco weed tree (solanum mauritianum) and severed the 30 centimetre trunk only to have it fall onto a wire fence and the butt end swing up to narrowly miss my nose. I didn’t mention this to anyone at the time, but still sweat when I think of it.

On the topic of tobacco weed or kerosene plant, when I first encountered it, it’s botanical name was solanum auriculatum but Dr Colin Little, an agricultural scientist who lived in Kerikeri, pointed out that the correct name was solanum mauritianum.

Colin Little, who I found was a honorary ranger, lived with his wife Margaret on Aroha Island in the Kerikeri Inlet made a habit of calling in to the Ranger Station at odd, mostly inconvenient, times. He had been in Kenya on a project whilst working for the FAO in Rome which gave him a common point of contact with myself. He was a controversial figure in Kerikeri who had few friends and tended to accost people in the street, especially young females, and ask inane questions. On one occasion he invited me and my family to lunch on what turned out to be a very hot day and he didn’t stop all day. He was a tall man with a long stride and quite exhausting, At one point he insisted in rowing over to the nearby Ladies Island. After that we kept a fund of excuses.

One issue that came between he and myself was the question of the safety of 245T. Little maintained that he had been a pioneer of the aerial spraying of the chemical and it was so safe that he was willing to drink a glass. I never saw this happen, but often wished that it would!

On another visit Len McConnell took me to the Mangingangina Scenic Reserve which comprised about 30 acres set on the Eastern edge of the Puketi State Forest at about 350 metres ASL. At that time the reserve was notionally controlled by a Board under the chairmanship of a local farmer John McIntosh. The board had employed a nearby resident, an apiarist, Fred Marley, to act as caretaker to clean and service the somewhat primitive public lavatories adjacent to the carpark. I found the reserve in a sad state with a modest system of tracks that were little more than muddy watercourses. There were two tracks, one entered and exited at the carpark after circling some stands of large old kauri, and the second traversed an area of regenerating forest and exited to the road seven or eight hundred metres to the South. There was considerable interest in the kauri and the reserve was quite heavily visited, but many must have been put off by the state of the tracks. A little reading suggested that tampering with the “bokau” or heap of decaying vegetation that lay around the base of the trees could damage their long term viability. A fungi lived in the bokau and set-up a symbiotic relationship with the tree, supplying essential nutrients in return for a supply of sugar. Consequently, destroy the bokau, destroy the fungi, destroy the tree.

Back in Kerikeri, things were beginning to move on the tools and equipment front. I flew down to Auckland to pickup an old Holden sedan and 16 foot runabout with an Evinrude 50 hp motor, the latter ex-HGMP. Neither were ideal for the job, but they enabled me to visit other areas of reserve without assistance from Whangarei.

The District Field Officer Whangarei, Tony Childs, suggested that I go to Matauri Bay and make myself known to Dover Samuels, an honorary ranger. He gave no specific reason for such a visit and Samuels was among a couple of dozen other honorary rangers in the district. So one Sunday morning I took the family and drove to Matauri Bay which is opposite Big Cavalli Island. I found Samuels was not at home, but left a message for him with Martha Broughton a delightful elderly Maori lady. That evening, Samuels rang me and told me that he did not want Kerikeri ‘historical’ people out at Matauri Bay where they had no business. I tried to explain that I was the Lands Department Ranger at Kerikeri and had been instructed to contact him, but he would not listen.

Some week later, Len McConnell arrived saying that Tony Childs had asked him to accompany me to Matauri Bay to again try to make contact with Dover Samuels. We drove to Matauri Bay and we were getting out of the Len’s utility, Samuels emerged from a building and straight away started to castigate us as colonialists who had no business there, Len tried to reason with him, but again he would not listen. To this day I don’t know why Tony Childs was so anxious for me to contact Dover Samuels, but I did come to know him later as a Whangaroa County Councillor when, in contrast, he was at pains to make himself agreeable.

Meanwhile I had been in contact the Labour Department to let them know that I could use some casual labour from the Temporary Employment Programme (TEP) and they started to send candidates for interview. They would be used mainly on clearing gorse, tobacco weed and other exotics in the Basin area, and so I was looking for labour capable types. Within a couple of weeks, I had six guys at work in the Basin. As an incentive to potential employers, the Labour Department not only paid the wages, but also provided transport, tools and equipment, overalls and boots.

One of the first group wasted no time in letting me know that he had applied for the rangers position and that he felt himself better qualified and more suitable than I — largely by reason of the fact that he had been born and raised in proximity to the Basin. Being election year, I had become quite heavily involved with the Values Party, principally in assisting the Hobson candidate, Richard Alspach, with his campaign. In general business at a Values meeting in the Hokianga, the convenor said that she had had a question from Kerikeri, asking the party’s position on the racist former South African policeman now employed as a Lands department ranger at Kerikeri. The meeting knew nothing about this individual and so I asked who had raised the question and was not surprised to find that it came from my employee, the unsuccessful applicant for the ranger’s position. Perhaps he was planning a re-run! When I revealed that I was the ranger at Kerikeri and that although I had visited South Africa, I had never worked there, the question was dropped amid some embarrassment.

Some weeks later, I was at the Marsden Cross Historic Reserve when I received an urgent message from Peter O’Hagan, the curator at the Kemp House, asking me to return to Kerikeri urgently. Peter said that he had seen one of the workers starting to cut down trees on the Sinel property and had assumed that he was following my instructions. He had had a loud altercation with the worker who had refused to stop the felling. I found one tree down and in the process of being cut up. The worker said that as a local who had spent all his life in Kerikeri he had a better feel for the area than I could ever possibly have and that he intended to complete the job of removing the trees. I summarily dismissed him for failing to comply with the lawful instruction and asked him to return the boots and overalls, The boots appeared on my desk a year later — worn out!

At this time I was visiting the more publicly accessible reserves in the district and beginning to understand the extent and immensity of the work needed to restore them to an acceptable standard. Most of the reserves had been neglected. Northland had a reputation for the variety and speed with which exotics would grow and gorse had made substantial inroads into many of the reserves and some remained unfenced and subject to stock incursions. In Kerikeri, eucalypts, wattle, tobacco weed and blackberry were also present, whilst at St Paul’s Rock Scenic Reserve adjacent to Whangaroa village a growth of wild ginger was expanding over the lower slopes.

A visit with departmental landscape architect Peter Rough to the Marsden Cross Historic Reserve on the northern shore of the Bay presented a sorry picture. As a student in summer employment with the department, Peter had done a design project on the reserve which was to prove a valuable resource but which, at that stage, was pie in the sky! The 30 acres, mostly on a very steep hillside, was almost totally infested with mature gorse with some younger stuff along the top boundary. There were a few wayward shreds of manuka, mainly along a stream bed which flowed down to the left of the Celtic cross. The reserve was unfenced from the surrounding farmland and infested with feral goats. Clearly nothing could be achieved by way of rehabilitation until the reserve was fenced and the goats removed.

Access to Marsden Cross was then through a series of grass paddocks from Rangihua Road and in the largest paddock we were astonished to find the ground thick with mushrooms. We stopped to pick a large box for Peter to take back to the Auckland office — on the premise that I would be back many times to take advantage of the find. In my fifteen years in charge of the reserve I never again found another mushroom!

Historically, next to the Kerikeri Basin, Marsden Cross is probably one of the more important sites in the country. It was here that Samuel Marsden landed in December 1814 and, on Christmas day preached the first Christian sermon on New Zealand soil. Marsden had sailed down from the Cavalli Islands in the brig Active accompanied by the chief Ruatara whose home Pa overlooks Oihi Bay. A mission Station was established, the first sale and purchase of land in this country was executed, houses and a school were built, and the first European child to be born in New Zealand was born on the site. The only signs of all this activity today, are the benched outlines of the buildings on the flat area above the beach. In the early twentieth century a Celtic Cross was built to commemorate the Mission Station and the early settlers. Above the cross, up the hillside, is a large stone engraved with the names of the missionaries and their families.

Around this time I accompanied the Commissioner of Crown Lands, Darcy O’Brien, on a visit to Ray Patterson the owner of Mataka Station who was then in his 80s, The visit was ostensibly to continue the negotiations and the possibility of the Crown buying the land owned by the Patterson family on the Purerua Peninsula. I cannot now recall whether the asking price was a quarter, or three quarters of a million dollars, either of which was a lot of money in the 1970s. I heard no more of this and some time later the land was bought by Bill Subritsky. The area was open grassland with patches of native vegetation in steep gulleys, and some gorse. In hindsight, it was probably as well that the sale to the Crown did not go ahead as we simply did not have the resources to restore such an area — and it would have been very long term and costly. The sale to Subritsky was to bring advantages and disadvantages in relation to Marsden Cross.

One of the attractive features of the Project Employment Programme (PEP) was that the Labour Department would supply not only labour, transport, tools and equipment, but materials for approved projects such as fencing, tracks and so on. I had previously met the regional superintendent of labour in Whangarei, John Ball, through the Values Party and we soon had an arrangement that he would send to me registered unemployed people for ‘work testing’. The work I was offering initially did not call for any special skills, just commonsense and a willingness to follow instructions, and so there was little or no reason to refuse the work. My PEP team gradually increased in size and among the referees I found some good people who attended regularly and worked — in contrast, there were those who were poor time keepers, or did not bother to turn up, either way, the work force increased and at last inroads were made into the weeds and unwanted vegetation in the Basin area.

On the former Veale sub-division, as well as the kerbs and drainage, the topsoil had been removed from the putative building sites and the felled eucalypt logs had been pushed into enormous piles on the slopes and roughly covered with spoil. These heaps were hazardous because as the soil collapsed chasms appeared in the piles. The logs proved to be extremely hard, resisted chainsaws, and so removing the timber promised to be a long term project. Contrary to instructions, one team of PEP workers had piled gum debris into heaps among standing trees and set fire to them. The heaps burned down, but the slightest breeze reignited the ash pile and fire had a habit of popping up many metres from the original site, presumably by burning through old root systems. Nonetheless, fallen vegetation was gradually removed and the fire hazard reduced. One feature of this area was the speed with which eucalypt saplings appeared and the rapidity of their growth.

As the former Sinel land was cleared of unwanted vegetation, so the visiting public started to take an interest in the limited walks available along the riverside and visitors were walking between Mrs Sinel’s house and the river bank. To afford Mrs Sinel some privacy, the only possible solution was a fence around the house and outhouses to enclose an area of about a quarter of an acre. A proposition was put to the Auckland office and consent was obtained to construct a fence, provided that the labour and materials could be obtained using the TEP. The project was approved by the Labour Department, a team assembled, and the materials ordered and the 1.8 metre solid paling fence constructed in tanalised rough sawn pine. A gate was built on the existing driveway which emerged somewhat dangerously near the river bridge.

At the same time a 3 metre square shed was erected out of sight to the rear of the house for storage of tools, fuel and an electric grinding wheel. The first workshop! About this time, Geoff Hearn a former British Transport Policeman joined the TEP team as a supervisor. What Geoff lacked in practical experience, he made up for with common sense and application. Shortly after the shed and grinder was installed, Geoff opened up one morning and was putting an edge on some slashers when the timber floor burst into flames. Fortunately we had put an extinguisher by the door and he quickly put out the flames. The sparks from the grinder had ignited some spilt petrol, Another lesson!

Mark Turner was also referred at about this time and became a team supervisor. Mark was a younger man with a background in design and architecture and soon made himself indispensable. Later, in the early 80s, he was appointed a Park Assistant and in 1987 became a Conservation Officer, In 2006, he remains employed at the Kerikeri Ranger Station.

Unbeknown to me, the Crown then acquired another five acres overlooking the Basin and immediately opposite the Sinel property. The land, owned by Mrs Nancy Pickmere, a luminary of the Society for the Preservation of the Kerikeri Stone Store Area, had for many years been used as a motor camp. Unlike Mrs Sinel, Mrs Pickmere was to retain ownership of her house and garden — so yet another fence had to be built. On the land were several ‘A’ frame huts which had been rented to campers and a rough replica Maori village, dubbed Rewa’s village. The area was also traversed by a footpath leading from some steps adjacent to the bridge and leading through to Kemp Road. Some 50 metres from the bridge vehicular access led to another house which had been used variously as a residence, craft shop and tearooms. Careful to leave nothing of value inside, I took over one of the huts on the new reserve as a temporary office.

A number of issues emerged from this development. I received an invitation from SPPKKSSA to attend one of their regular meetings. At the meeting it soon became clear that the committee regarded the ranger as a servant of the Society, literally at its beck and call and subject to direction by the committee. Further, that the Crown having bought the Pickmere land would now assume responsibility for the collection of materials and maintenance of Rewa’s Village. As a reward for all this, the Ranger would become an ex-officio member of the committee. The denouement came as something of a shock to the committee and they were invited to put such proposals to the Commissioner — I don’t think that they ever did.

One morning I was sitting in the A frame ‘office’ when I noticed an elderly Maori gentleman called George who I knew lived in a sleepout behind Mrs Pickmere’s house and who acted as her gardener. George had made several trips into the reserve when I stopped him and asked what he was doing. It seems that ‘Nance’ (Pickmere) had told him to remove some natives that the Society had planted, and replant them in her garden. ‘Nance’ said that she had planted the plants on her land and was simply removing a selection for her garden — she was irate when I pointed out that she had also sold the land to the Crown and that it was an offence to remove any vegetation from a reserve, no matter who had planted it. This was the first of many contretemps involving Mrs Pickmere. Some weeks after the fence around her house was completed, 1.8 metre closed paling facing the reserve and post and wire facing the river, I was alerted to the fact that a rough stile had been built over the latter and a new track cut down to a small jetty, Removal of the stile and closure of the track resulted in a complaint to the Director General. There was adequate access to the jetty through Rewa’s Village, but it seemed that this was not private enough for Mrs Pickmere whose delight it was to swim from the jetty — although I never once witnessed such an event. Her complaint was rejected.

By 1977, when George McMillan succeeded Darcy O’Brien as Commissioner at Auckland, things were beginning to move in the Basin and a derelict area of Crown land had been reclaimed. This was a smaller area of mainly bare land at the top of the hill, just above the Playcentre and Scout Den, extending from Landing Road to the river and which I had assumed was private land. A neighbour had certainly used it for parking vehicles and for large rubbish fires. He was gently asked to quit and a few weeks later we hitched the “A” frame that I had been using as an office to a tractor and dragged it off the former Pickmere area, across Landing Road and sited it in the corner of the “Ranger Station”. It was soon joined by the tin shed from behind the Sinel house which became a tool shed and fuel store. Electricity and telephone were soon connected, About this time too, the Holden saloon car was replaced by a new Isuzu utility with a fibreglass lid over the tray. This proved to be not the ideal vehicle, but infinitely superior to the job than the Holden.

For some weeks I’d been receiving abusive telephone calls at home at about 5.30pm from a Charlie Smellie who never quite managed to say what he wanted to say. Finally, I told Smellie that I had recorded his message, and he immediately rang off. The following morning I transcribed what I had on tape and consulted the Kerikeri postmaster, Frank Lippett, who confirmed that such nuisance calls, especially when course language was used, contravened the Post and Telegraph Regulations. After alerting the local constable, Alec McKay, I went to Smellie’s shop and told him that his calls to my home were disturbing to me and my family and that unless he desisted I would lodge a complaint under the P & T Regulations. When he agreed to desist, I asked him what he wanted. His response was that I didn’t acknowledge him in the Street…!

Then some time later, George McMillan rang me and said that he would be meeting Neil Austin, the National MP for Hobson, at my office the following day to deal with a complaint by a local resident. However George said that the gist of the complaint was that Smellie, as spokesman for the local branch of the National Party, believed that in using unemployed people in the Kerikeri Basin I was wasting taxpayers money.

I immediately compiled a list of local businesses from whom goods and services were bought on a regular basis and extracted from my records a rough sum of monthly payments. I also calculated the sum of monthly wages paid to PEP workers and pointed out the local businesses that benefited from these payments, among others: the service station, supermarkets, and not to mention the Homestead Hotel. Charlie Smellie owned one of two local supermarkets. I also recalled that when I started to employ PEP or TEP workers, the Labour Department had said that the schemes were as much about injecting funds into the local economy, as about providing employment. The next day I handed this material to George McMillan who smiled and said, “I thought you might do this…”. Neil Austin duly arrived and George handed the papers to him, he confirmed that it was the Governments intention to boost local economies. Smellie arrived on his motor scooter and received short shrift. I understand that he received a roasting from the local branch of the National Party.

Meanwhile at Mangingangina work was proceeding slowly but surely under PEP supervisor Doug Clark. After a lifetime of practical experience, Doug was nearing retirement age and loved to regale the crew with tales of the siege of Tobruk. Among his team was a boy from American Somoa, Wayne Charles Maczaritis, who was staying with his sister in Kerikeri. The team included several Maori guys and once they found that Wayne, aged about 16, was not too happy in the forest they had a lot of fun listening for ferocious wild dogs, Wayne eventually heard them himself and stuck close to his work mates. He was otherwise such a fantasist that Maureen was moved to forbid our boys from having any contact with him. He was certainly very troubled and obsessed with firearms. This would not be worth a mention, but for the fact that some years later Maczaritis was convicted of the murder of a man and a woman in the Lindiss Pass in the South Island.

Another work programme employee had tenancy of a Forest Service house at Puketi. Arriving home one afternoon he found his wife in flagrante delicto with a family friend. He stealthily collected his shotgun and murdered the interloper.

Over the years we had a mixed bag of workers under the several work schemes, a half a dozen or so degree holders and one Doctor of Philosophy. The latter, an American, left me a reference when his departed.

On the Purerua Peninsula the newly appointed farm manager at Mataka Station began vigorous moves to rehabilitate the farm. New roads were constructed, fencing installed, a range of exotics and natives planted, pastures top dressed, water reticulation improved, and of the greatest threat to Marsden Cross, and intensive campaign of aerial weed spraying commenced, “Prickles” de Ridder the Marine Helicopters pilot had formed the habit of emptying his tanks over gorse at the top of the reserve, and at one point established his depot in the reserve near the Cross, using water from the small stream that emerged from a gulley. I arrived at the reserve one day to find four 40 gallon drums of 245T stacked by the stream with one leaking concentrate into the water.

I suspect that he was in cahoots with the farm manager who believed that the department should clear the slopes above the Cross and replant with natives. Indeed Harold Jacobs and myself met Bill Subritsky and the manager at the reserve where this view was expressed in the most forceful terms. Fortunately, Bill Subritsky was open to an alternative view and agreed with the departmental position that the gorse on the slopes could be used as a nursery for regeneration with some planting near the foreshore. I might add that a visit to the reserve in 2005 more than vindicated this approach and showed that re-growth of leptospermum species on the steep hillsides was very effective in suppressing gorse, The other native species planted about the Cross and in the gulley showed good progress.

Finally, funding was approved for ring fencing the reserve and a contract was let to Dennis Grey of Kerikeri, Dennis built an excellent fence which, apart from a few broken battens, still stands, He worked alone and I was concerned at some of the gradients on which he used his tractor, but he completed the project without incident, The farm undertook to liaise with Dennis to round-up the feral goats before the fence was completed, but several dozen goats remained. I acquired a .223 Brno rifle and over a period of some month the goats were eliminated.

During this time, Bruce Flintoff, working alone at Marsden Cross contrived to cut his leg quite badly with a chainsaw, After waiting for a couple of hours, he managed to attract the attention of one of Fuller’s tourist launches which took him to Paihia. Bruce, a young man, was something of a character and preferred to work alone and I was foolish enough to indulge him. The moral of this tale is that he should not have been working alone anywhere and this became the invariable rule from this point.

I was bound by the Reserves Act and departmental policy, but this seemed hard for some people to understand. One elderly gentleman from Coopers Beach who described himself as a retired naval chaplain visited me several times stating that he wished to be appointed honorary caretaker at Marsden Cross. He also produced a plan and a drawing of what he described as a tree cathedral. This consisted of six parallel rows of trees, three on each side, climbing from the foreshore to well up the slope behind, with kauri to represent New Zealand, eucalypts Australia and oak trees the United Kingdom. The drawing depicted mature trees, with kauri around a thousand years old, and the oak not much behind. He also urged that Samuel Marsden should be elevated to the position of patrol saint of New Zealand!

Next up was a lady with a more practical proposition, but who did not seem to understand that there was nothing I could do for her. She visited me several times, and would ring on Sunday evenings around 8.00pm and regale me at length with the latest on her proposition. Patricia Bawden was a deaconess in the Anglican Church and had had a vision that God wanted her to set up a Christian Centre up the valley to the West of Marsden Cross. At the time she was at loggerheads with the land owner, Bill Subritsky, a charismatic Christian, who for some reason did not support her idea. Leaving no stone unturned she had addressed her proposition to the Queen, Prince Charles, Princess Anne, the Prime Minister, the Governor General, this list was endless, but apart from a polite reply from each she could gain no traction.

Many years later, after my departure, a Christian Center was sited off the approach road to Marsden Cross.

Back in the Kerikeri Basin, I had regular visits by Harold Jacobs, supervising ranger Auckland, the two assistant Commissioners, John Brent and ‘Aka’ Conway, the land utilisation officer Don Millar, planner Bob Drey and the departmental landscape officer, John Hawley — the latter two invariably together and their purpose never entirely clear.

It had been decided that the area adjacent to Playcentre and the Scout Den would become the site of the Kerikeri Ranger Station and the design and landscaping was entrusted to architect, Brian Halstead. The site would comprise a large pole supported workshop with a vaguely Maori theme, with an enclosed tool store at one end and four open bays for vehicles and implements. An office some twenty metres to the west of the workshop, and a three bedroomed ranger’s house and garage about fifty metres beyond, perched on the bluff some one hundred feet above the Kerikeri River. At this stage I had very little say in the design and was just pleased to at last have a base, however drawbacks soon became apparent, not least in the matter of security.

News of two further acquisition came at around this time; 21 acres on the right bank of the Kerikeri River from Stan Booth, extending from Fairy Pools and the boundary of the Beer property to the rear of the Kemp House land. On the left bank, Ken Proctor had subdivided his farm from which the Crown gained the river margins, of varying width, extending from just above Rainbow Falls to the boundary of the new ranger station. The boundary of the latter was calculated to roughly follow the crest of the river valley to take in land unsuitable for agriculture or sub-division.

Although in a state of neglect, the Booth property showed signs, including remnants of dry stone walls, of earlier agricultural usage and it did hold the site of the first use of a plough in New Zealand — although the precise location of that event remains uncertain. At the time of acquisition however it was overgrown with wattle, patches of gorse and thickets of blackberry and remnants of ti tree. Although there were some signs of the former hydro electric facility, including a water race from Rainbow Falls, most of the Proctor river margins was too steep and awkward of access and so had never been used. In places, the vegetation and fallen debris was almost impossible to traverse, indeed, my first walk from Rainbow Falls to the Basin took some six hours through the jungle.

It was around this time that that I first heard the suggestion that some of those from who land had been bought by the Crown at market price, had donated their land, Amusingly, those named, made no move to deny this suggestion and obviously derived some satisfaction from the idea. Later the local press unquestioningly took up the idea of mass donations of land. At that time, the only ‘donation’ of land had been that by Earnest Kemp, who gave the Kemp House and garden to the Crown. The Stone Store was later sold to the Crown by his descendents for a paltry sum. There was an element of donation is some areas of the river margins adjacent to the Proctor property, and later Mr & Mrs Gilbert Parmenter gave about 5 acres in the valley behind their house on the Stone Store Hill. There were no other donations of land.

North of the Bay of Islands, a number of reserves in the Whangaroa County, hitherto administered from the Kaitaia office, were transferred to Kerikeri. These included the St Paul’s Rock and Ranfurly Bay Scenic Reserves, Big Cavalli Island and Mahinepua, This represented not only a substantial increase in area, but in responsibilities and demand for resources. The Whangaroa Harbour had almost as a long a history of European settlement as the Bay of Islands, and was the scene of the burning of the brigantine Boyd and the massacre of crew and passengers in October 1809. It had been said that the harbour was big enough to shelter the entire 1914 British Grand Fleet and on New Years Eve each year it looked like it!

The presence of several hundred yachts and boats of all kinds always gave some cause for concern, but when, at the stroke of midnight, they discharged their safety pyrotechnics in a massive display, one held one’s breath. The undergrowth in many places by this time was tinder dry and just waiting the spark as paraflares drifted on the breeze, I spent almost every New Year at Whangaroa and fortunately I saw only one serious fire and that was not on Crown land. On several NY’s eve I visited every boat handing out a brief pamphlet emphasising the danger of flares and fire. I was careful to do this early in the afternoon, but even so quite a number of people were drunk and several objected to my admonition. I recall pulling alongside the gangway of one large motor yacht to be confronted by the Prime Minister, Rob Muldoon, lolling in a state of dishabille.

In Lane Cove off the Western Arm of the Whangaroa, stood a three roomed batch built in kauri and belonging to the timber milling family, the Lanes, of Totara North. Shortly after taking over the area, I had a phone call from the Commissioner saying that he would like me to take him to the Lane Cove Cottage which had just been taken over by the Crown. When he arrived at the Totara North boat launching ramp, I was surprised to see the Assistant Commissioners, Brent and Conway, with him. There was an air of excitement among the three and I gathered that they were interested in a large heavy kauri table that had been seen in the cottage during the take-over negotiations. I should have remembered that at the time the tide was out and on low water springs, so that when we arrived at the cove there was nothing for it, but to ferry each ashore on my back! A key was produced and with mounting excitement, the door was opened. No table!

Back in Kerikeri, the TEP/PEP workers were proving to be both a blessing and a headache, A blessing in that steady progress was being made in the Basin on clearing unwanted vegetation on the newly acquired land. Some of the work referees were from the local Maori community and Te Tii village. The latter were mainly from a couple of well-known dysfunctional families ranging in age from mid teens to early thirties, which brought its own problems of attendance and punctuality. It could be almost guaranteed that the Friday after payday would be an unofficial holiday. Several times on Thursday afternoons I had to visit the Homestead Hotel, stand in the bar doorway and warn the crew that if they were not back at the Ranger Station within 15 minutes, not to bother to return at all. On one of these occasions the door of a car was opened to reveal a 16 year old totally incapable and vomiting — it seems that he had been fed ‘micky finns’ through the lunch hour by the others, who thought it a huge jest.

One day, several members of one family did not appear at 8.00am and so I rang to tell them that if they were not in the yard within an hour, they should not bother to return at all. Shortly, the father, a highly respected elder from Te Tii, entered my office, thumped the desk and told me my fortune, complaining that I was not in a position to direct his sons. Nor, I responded, was he in a position to enter my office and abuse me. I repeated my warning that if his sons had not appeared within the hour, then they should consider themselves dismissed. I’d rather hoped that they would default, but later in the morning they straggled in. This family had a very bad reputation in Kerikeri and were alleged to be regular thieves trained by their father. Within a year, the eldest, Fred, had killed himself by crashing a car into a bridge abutment.

At midnight one Saturday, the bell rang and on opening the door I found two of the Te Tii boys somewhat the worse for wear and hoping that I could let them have some petrol, promising that they would pay me on payday. Pointing out the hour and the fact that it was not my petrol did not impress and so in the end I let them have sufficient to reach home, on condition an equal amount was to be returned on payday. I’m still waiting! This happened several times until I read the riot act. Then, the old tin shed was broken open and petrol stolen. It did not take much imagination to guess the culprits, but proof was a little harder to come buy.

Eventually the station acquired two 400 litre bulk tanks, one for petrol and one for diesel. The tanks had cone shaped bottoms with a drainage plugs at the tip and it was not long before these too were attacked. The tanks had no provision for security and so flanges were welded to the drainage plugs and the tank bottom to allow for a padlock, and to the metal ends of the fuel delivery hoses which were then padlocked to the support frames. I could never understand why the rubber delivery hoses were not cut, but they survived intact. Later when it proved necessary to install an alarm system for the workshop, office and house, the old tin shed was also included with a door pressure pad — though it would not have been difficult to have levered the corrugated iron off the frame anywhere with the right tools.

An ‘L’ shaped open grass area of about three hectares adjacent of the former Procter property was set aside to become the Rainbow Falls Scenic Reserve complete with a carpark, a public lavatory, tracks and two view platforms. The reserve would also provide access to the proposed track to extend all the way to the Kerikeri Basin. Harry Turbott was commissioned to do the design. It was decided that, except for an open grassed area at the head of the river track, the reserve would be planted in a mix of native plants. From just above the falls, the now derelict hydro race ran through the reserve to exit near the road gate and it was decided to retain the race intact.

A carparking loop extending for about 75 metres into the reserve was tar sealed leaving a central dumbbell shaped grassed area into which was to be planted a grove of ‘sacred’ puriri. Under PEP supervisor Marshall Rihari a start was made on the chain link fence extending from the road gate to the river just above the falls following the boundary with the adjoining orchard property. The fence was topped by horizontal 150mm poles, Marshall Rihari proved to be the exception to the rule and became a reliable and hard working member of the team. I was surprised some months later when he tendered his resignation saying that he wanted to save his wages, but that it was impossible living with his wider family and that he proposed to move to Auckland.

Having completed the new track at Mangingangina the team under Doug Clark shifted to Rainbow Falls to construct the tracks, and to assist Terry Toft and Graham Hutton with the construction with race foot bridges, the two view platforms and the public lavatory. The platforms were designed by Harry Turbott and that over the falls basin was quite large and tied back by means of heavy poles to kingposts set firmly into the ground beyond the hydro race. The poles were rebated and secured by 10mm galvanised coach bolts, There were numbers of departmental visitors during this period, among them Harold Jacobs who was concerned that the platform be adequately anchored back to the kingposts so as to prevent any forward movement. At that time, the view platforms were the largest construction project undertaken, demanding a lot of timber, 8 inch nails and so many coach bolts of varying sizes that I began to worry at the cost.

Arrangements were made to obtain several thousand native plants from the Lands and Survey plant nursery at Taupo. In the winter, several trips to Taupo became a regular chore using a two deck adaptation for the Daihatsu truck and a specially constructed trailer. These trips continued until the nursery contracted a plant delivery service in the late 1980s. In the meantime a shadehouse was constructed to the rear of the Ranger Station where plants were held, not only for Kerikeri projects, but also for other stations. The fifty metre square shadehouse was fitted with a misting irrigation system and divided into discrete bays for holding stocks for delivery elsewhere. When biological integrity became an issue, local seeds and cuttings were collected by Richard Toft who prepared them for delivery to Taupo. He also propagated some stock in a small shed built adjacent to the Shadehouse. For a few years after the late 1970s plantings, some of the natives at Rainbow Falls struggled and it proved necessary to apply water over several summers.

Rainbow Falls reserve like so many spaces unattended at night started to attract campervan or mobile home types who would set up their home from home, erecting tents beside their vans, tying clothes lines between saplings and chaining dogs to trees and, on some occasions, lighting a camp fire, They were not easily moved on and sometimes it proved necessary to seek the help of the local constable. Signage had no noticeable effect and so finally it was decided to erect gates at the entrance on both sides of the carpark loop. The gates were closed at sunset and opened first thing which did not entirely solve the problem, but certainly helped. One evening at dusk I found a car parked, but could not locate the occupants. After a repeated search I finally saw them, a male and female, both naked, on the rocks immediately above the falls on the far side of the river. What is it about the Kerikeri River? I left a note under their windscreen wipers and when I returned an hour later they’d gone.

In 1979 the department published a report by a traffic consultant on the possibilities for removal on the incongruous single lane reinforced concrete bridge in front of the Kemp House. The report by Russell Dixon, offered three possible alternative bypass routes upriver and out of sight from the Basin. The suggestion stirred an immediate and unsympathetic response, not from former colonial settlers who remained largely indifferent, but from long time residents in the Riverview area. Several of those, some illuminati of SPOKSSA, argued vehemently and with all seriousness that removal of the bridge would remove their ability to walk down to the Stone Store in the morning to buy a paper and milk! Traffic, including heavy lorries, stock trucks and tour busses, travelling down the Stone Store Hill all passing within metres of the wall of the Stone Store and turning left on a right-angled blind corner. Quite apart from the public safety implications, the Historic Places Trust has well-justified concerns about the long term effect of vibrations caused by the heavy traffic on the fabric of the building. The Trust did tests which confirmed their suspicions about possible damage to the building. The single lane bridge adds to congestion and potential hazards, and all the locals could think about is their own convenience!

Typical of the attitude of some of the people living in the vicinity of the Basin was the issue of kiwi. When I moved to the ranger station in 1977, one could hear kiwi calling in the reserves at night. I often heard residents boasting that there were kiwi in the bush at the foot of their garden. Yet several insisted on walking their dogs in the reserves, holding that it was their right to do so. I argued that apart from the fact that it was illegal, once they slipped the lead the dogs were free to roam at will over the entire reserve and into corners never entered by humans. My worst fears were confirmed when children from a Christian school situated on the reserve boundary started to bring me dead Kiwi that they had found around the Basin reserves. All showed tooth marks that could only have been caused by dogs. The department seemed curiously reluctant to take action and so ultimately I prosecuted three or four of the most persistent offenders under the Reserves Act and secured convictions in the Kaikohe District Court, Later. I was criticised by the departmental solicitor, Russell Wells, who held that prosecutions could only be brought where bylaws applicable to the specific reserve existed. He may have been right, but neither the court nor the defendants’ solicitors ever raised any issues. Indeed one of the defendants engaged no less than three different solicitors and in the end he pleaded guilty and was fined $200.

Signage of reserves in the Kerikeri district was largely nonexistent, or primitive and uncoordinated. After some unsuccessful attempts at hand routing boards it became apparent that a more consistent and practised method was necessary. We acquired a Letraset style book and from it selected a type face that lent itself to routing into timber.

Mark Turner proved to be a fount of knowledge on layout and letter spacing, or what he called optical character spacing, and so it was left to him to draw up tracings, upper and lower case, and in several sizes. The character tracings were then transferred to pieces of 12 or 15 millimetre marine ply of uniform height which were then cut out using my Dremel scroll saw. The character billets were next trimmed in width to facilitate the correct spacing between letters when set into words, A jig was then constructed using aluminium channel and timber in which the character billets could be inserted in order to set up into words.

To achieve consistency through the district, 250 by 50mm pinus clears were chosen for reserve title signs, single or double boards, and rebated into selected round, 150mm, tanalised posts. Directional or information signs were routed into 150 by 50mm pinus clears and also rebated into round tanalised posts, generally set lower than the title signs.

The posts and timber boards were left unpainted and a dark “conifer” colour was used to pick out the back of the letters, Aluminium National Park and Reserve plaques were epoxied and riveted into appropriately shaped rebates.

One aim of the jig and letter template system was to enable anyone to work in the sign shop after minimal instruction. This idea worked well although some staff showed more aptitude to the task than others. The system owed much to trial and error and relied on the co-operative efforts of Mark Turner, Terry Toft and others.

Inevitably as the eye-catching signs were erected around the district we began to receive requests from organisations, clubs, schools and the like, to manufacture signs for them. In the main, these requests were rejected, but we then started to get requests from other districts which were met as time allowed.

Huaraki Gulf Martime Park (HGMP) had a problem with wharf signs which were usually bolted to piles, but the pinus boards did not stand up too well to the sea and weather. After some head scratching we had some heavy laminated boards manufactured by a firm in Auckland and prepared the requisite signs using this material. The theory being that using small billets of timber laminated together using epoxy to produce boards of the requisite size should obviate splitting and offer better weather resistance.

Later, designed by Harry Talbot, a large finished sign was produced for the interior of the new Bay of Island Park Headquarters visitor centre at Russell. The selected timber was prepared, sanded, sealed and then serially spray painted in auto enamel in a deep blue, The large letters, “Bay of Island Maritime & Historic Park” were in a ‘V” profile which differed from out regular cuts, and were to be finished in gold leaf. However, gold leaf proved hard to come by and finally the letters were finished in gold paint and looked good.

All this activity necessitated further expansion of the facilities and an end bay in the workshop was enclosed for sole use as the sign shop. A section of the implement shed which had been built on the other side of the yard was converted to racks designed for the storage of the timber clears.

Sometimes it was necessary to add information to signs which was not easily done using our standard method of routing into timber, There was a limit to the minimum font size that could be achieved with this method, As an experiment, we had some notices commercially engraved into formica which were then set into rebates using epoxy adhesive. Because some plaques were damaged, mainly at the corners where people had tried to lift them from the timber, we later also secured the corners using round head aluminium pins.

The Formica was available in a number of surface colours with contrasting under layers, but we used mainly black top with white base. Once the practicality and durability of this material was proven in use, the station acquired its own professional pantograph machine. Staff were able to successfully operate the machine with very little instruction.

On the topic of durability of the Formica signs, when visiting Kerikeri in 2005 I observed that many of the original signs were still in use some twenty years after installation.

As I became more familiar with the outlying reserves so more fencing needs became apparent and were added to the annual budget bids. Two reserves which were difficult of access necessitated the use of helicopters to fly in fencing materials. At Ranfurly Bay Scenic Reserve semi wild stock were encroaching from Maori land overlooking Taupo Bay and a fence was constructed from Ranfurly Bay to the Ocean to exclude these animals.

At Okuratope Pa Historic Reserve at Waimate North, similar stock incursions had virtually removed the understorey about the reserve and the Pa earthworks were suffering. Fencing materials were trucked into the reserve and distributed by a helicopter to the steep slopes down to the river below the Pa where a TEP gang did a sterling job of construction.

Okuratope Pa is almost immediately opposite the Mission House at Waimate but access is across a paddock in private ownership and the Pa itself is almost invisible under mature vegetation, During one of the Parks summer programmes I met a group on interested people at Waimate to guide them into the Pa site, Everything went well until we returned to the vehicles when I became aware that a boy in the group had in his possession a 30 centimetre stone adze which he’d found protruding from the Pa earthworks. Both parents were present and were not happy when I pointed out that the adze was subject to the provisions of the Reserves, the Historic Places, and Antiquities Acts and that I was obliged to seize it. They declined to hand it over. After some discussion they remained adamant that their son had found the adze, therefore it was his to keep. Dangerous decision, I opined, because the Pa and anything found on it was deemed to be strongly tapu. I had not thought that they would fall for that line, but the adze was placed on the seat of my truck faster than lightening! I understand that the artifact remains on display in the Mission House. One problem was that the boy was, and remains, a close friend of my sons and I knew the family well.

Shortly after the Ranger Station compound was completed we had a visit from the Minister of Lands, the Honourable Venn Young and his wife. They were accompanied by the Land Utilisation Officer from Auckland, Don Millar, who had stayed with them the previous night at THC Waitangi. As we walked through the gate I could not believe my ears when I heard Don Miller comment that the yard bore a strong resemblance to a Nazi concentration camp. I explained that it had been necessary to add the two metre wire mesh fence for security after a string of thefts, and that the fence would be virtually invisible when the plantings matured.

At the same time, an alarm system was installed with sensors in the main workshop — which was now enclosed — the office, the old fuel shed and the ranger’s house. Whilst there was a siren and flashing light on the workshop, the system had the facility to switch to silent mode with a whistle in the house only. Very soon after it was installed the alarm sounded in the house at about 2.00am. I entered the yard through a small hole that had been specially cut in the fence and could find no sign of an intruder. This happened several times and I was about to report the system as faulty when we found the culprit, a possum! The only possible place of entry was through a narrow gap in the exterior cladding around the structural roof supports, This was blocked and there were no further alarms — until… The alarm was triggered in the early hours one morning and again there was no sign of an intruder. This time I did report a fault and the technician concluded that the problem was spiders crawling across the sensor in the office. He reduced the sensitivity and placed moth balls inside the sensors. Problem solved.

The size of the TEP/PEP teams waxed and waned over time and we were obliged to adjust our activities to the available hands, but work continued throughout the district, though generally not on the island reserves, For some six months after the light was automated we did have two hands stationed in the old lighthouse keepers’ house at Cape Brett, Acquisition of this reserve completed the final link in the Cape Brett track and provided an overnight base for hikers.

Mark Turner was appointed Park Assistant, and Terry Toft and Graham Hutton became staff carpenter and engineer respectively. The increase in specialist staff meant more equipment and within months we had a well equipped workshop including, finally, a dust extractor unit.

Terry was from a background in glass and had owned a business in Levin, He was a self-taught carpenter and joiner, but was meticulous to a fault. His skills were soon in great demand.

Graham had formerly owned a light engineering business in Kerikeri, a business we had used for various tasks with consistent satisfaction. Among other items, Graham had constructed a heavy two wheeled, tractor towed trailer for the Kerikeri Station, This led to the construction of a tandem wheeled trailer for use about the Kerikeri District and in particular for transport of plants from the nursery at Taupo, The trailer was built to professional MOT standards and galvanised in Whangarei before the suspension and wheels were added, This led to a request by Harold Jacobs for six identical trailers fro other stations around the North Auckland land district.

Among other projects jointly carried out by Terry and Graham, were the construction of the public lavatories adjacent to the Kerikeri Basin carpark. The lavatories, designed by Harry Turbott to blend into the landscape design and to provide for ease of cleaning and maintenance, were to have a timber shingle roof. Enquiries revealed that the only shingles available were imported from North America at a cost that would have blown the construction budget. After some experimentation we acquired some 1.8 metre by 150 by 12mm rough sawn tanalised fence palings which were cut into 30 centimetres lengths. These were spaced along the gutter line starting at the bottom of the roof and fixed with a single nail. Then each successive row of shingles was offset to equally lay across the joint below and so on to the ridge. No roof lining was used and the shingles were visible from inside the unit. The roof was found to be intact and sound twenty years after installation. A similar, but smaller facility was constructed at Rainbow Falls Scenic Reserve adjacent to the carpark.

Over the years, I would be accosted by visitors, mainly Americans and Europeans, at the reserves seeking a “rest room” — I couldn’t resist asking them if they were tired — and then, oh you mean the public lavatories!

Graham left us after a couple of years to take up a position as a shift engineer at the Affco meat works at Moerewa where, not many months later, he lost his life when a pipe joint burst ejecting chlorine directly into his face.

The following is a report I submitted to the Commissioner of Crown Lands Auckland on 10th April 1981 after the flash flood that occurred on the night of 19/20 March.

During the evening of Thursday, 19 March, 1981, in nil-wind conditions, an intense electrical storm settled over the catchments of the Kerikeri, Puketotara, Waipapa and Waitangi rivers giving moderate to heavy falls over six to eight hour period, Up to 375 millimetres of rain were recorded at some points in the catchment.

I crossed the bridge at the stone store at about 11.00 PM and noted almost Normal River flow, At 1.25 AM I was awakened to see water in the Kerikeri River below the Rangers house at 30 to 40 feet above normal levels. The reserves to the west had more the aspect of a lake, and I noted that mature Totara which stood on a point opposite the house had already gone, Based upon what I later saw I believe that by this time the peak of the flood had already passed.

At the Stone Store, I found water on the north side of the bridge up to the tea rooms car park access and estimated 8 to 10 feet of water over the bridge, The 11,000 volt power lines across the basin were down. I found phones still working and unable to raise the local police station was able to contact a constable at Taheke and have him notify all relevant authorities, I alerted park assistant Mark Turner and two other staff members and contacted the chief ranger Russell by VHF radio.

At about 1.45am Mrs Pat Sinel was removed from her house which is situated in the reserve about 75 metres above the Stone Store bridge and on the river bank, To my knowledge at that time, Mrs Sinel was the only local resident in immediate danger.

Sometime after midnight on the 20 March 1981, probably about 1am, Maureen woke me and said she thought I ought to take a look out of the bedroom window. The Kerikeri River was in spate and the reserves on the opposite bank were completely covered with water giving the whole an appearance of a lake. A large Totara which stood near the river on the opposite bank was gone.

Although heavy rain was still falling there appeared to be a curious light illuminating everything, possibly a reflection from the water.

My immediate thoughts were for Mrs Pat Sinel whose house stood on the riverbank just above the bridge. By this time my sons, William and Michael, were awake and together we collected the Isuzu utility and drove cautiously down the hill towards the bridge. I immediately noted that the 1100 kV powerline which spanned Kerikeri Basin were down and laying across the road. I reasoned that since they were down there was bound to be a break in the line and that the power would be off. We returned to the Ranger Station and collected the 12 foot aluminium dinghy.

When I returned to the observation point on the road about 100 m from the bridge I found Mark Turner and the Woods boys, David and Kenny, were already present. We placed the dinghy in the water and I called for a volunteer to come with me to the Sinel house. After some hesitation, Kenny volunteered to accompany me.

Mark Turner and the boys urged me to use the 4 hp outboard motor, but I reasoned that if the motor failed or we lost the prop then we would be immediately swept around the end of the bridge where the road had been carved away. I proposed to use short sharp strokes on the oars a technique known as pulling Navy fashion. Kenny and I set out and I soon found that boulders of various sizes were strewn across the reserve. The main force of the water was following the course of the river and the water on the reserve amounted to a backwash off the cliffs just above the Kemp House. There was a current, but it was manageable under oars. As we progressed, I asked Kenny to remove my boots.

When we reached the timber fence surrounding the house, we found that it was still standing but that the depth of water enabled us to grip the top of the fence and pull the dinghy along toward the river. As it would be necessary to pull the dinghy around the end against the full force of the river current, I knew this would prove to be the most crucial part of the job. We managed this and polled the dinghy across to the bedroom window in the slack water in the lee of the house.

The window was open, but I could not see inside and called out, to be answered by Pat Sinel who said that she was perched on top of a wardrobe. I could feel the house moving in the force of the water and shouted to Pat that she should come to the window as quickly as possible. It seemed to me likely that the house, which was constructed out of pre-war MOW huts, would break free and be swept down to the bridge. Pat dithered, worried about her dog which was nowhere to be seen. Finally, we had her in the boat and set out to return to the road. As we cross the reserve Pat told us that when the flood hit, she had climbed onto the wardrobe, but after a bit had stepped down to collect an ashtray! We reached the road without further trouble, whisked Pat up to the Ranger house and gave her a good tot of whiskey.

At Waipapa Landing one house was swept down the river out into the inlet and one person was lost. From the road I could see a person by the houses on the far shore flashing a lamp, but it would have been impossible to cross the river.

We found the Waipapa Road and the adjacent land covered with water and at the Rainbow Falls Scenic Reserve the whole was covered in water with the river shooting in a solid jet horizontally for some distance from the top of the cliff.

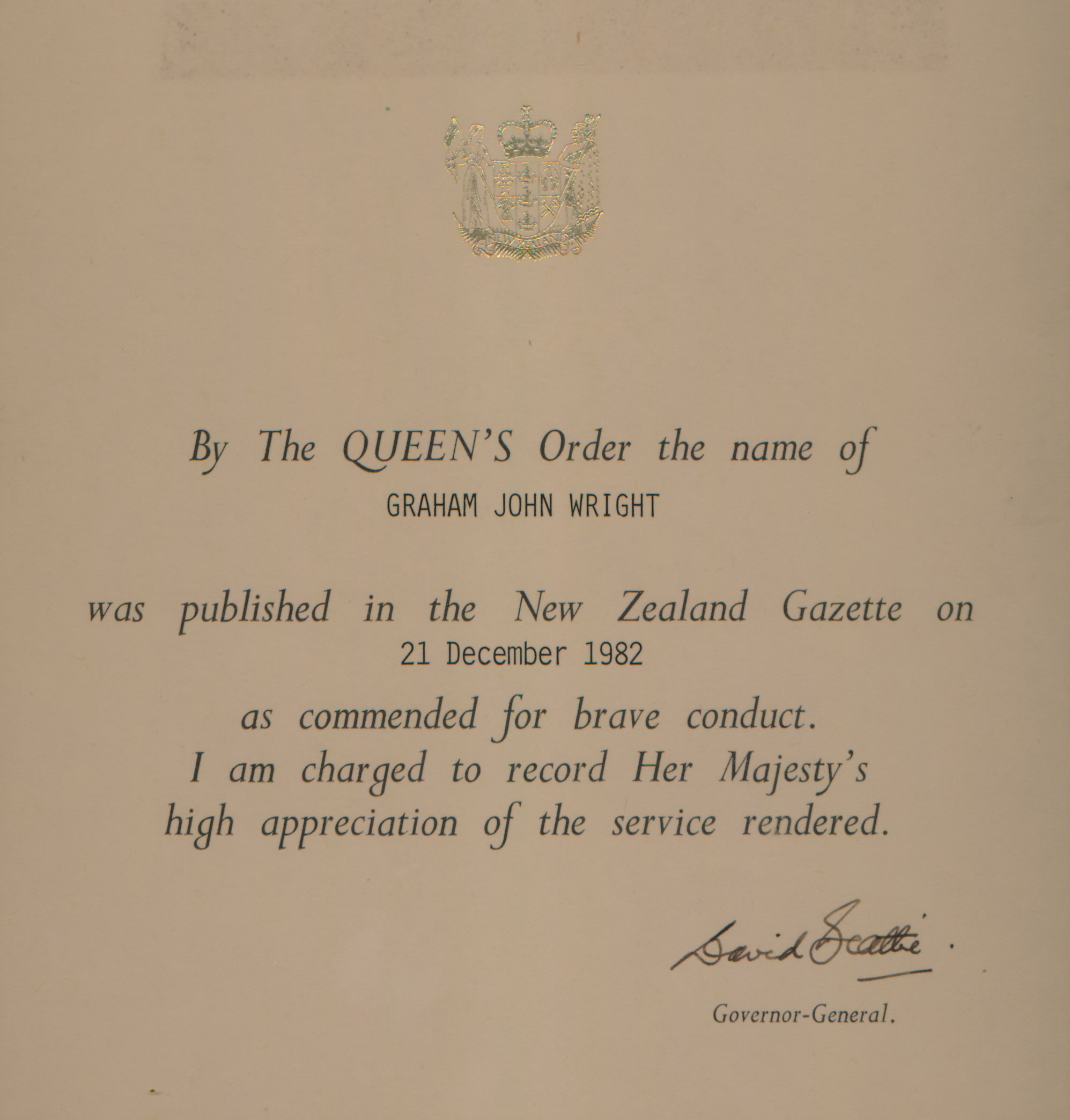

Kenny Wood also received the award.

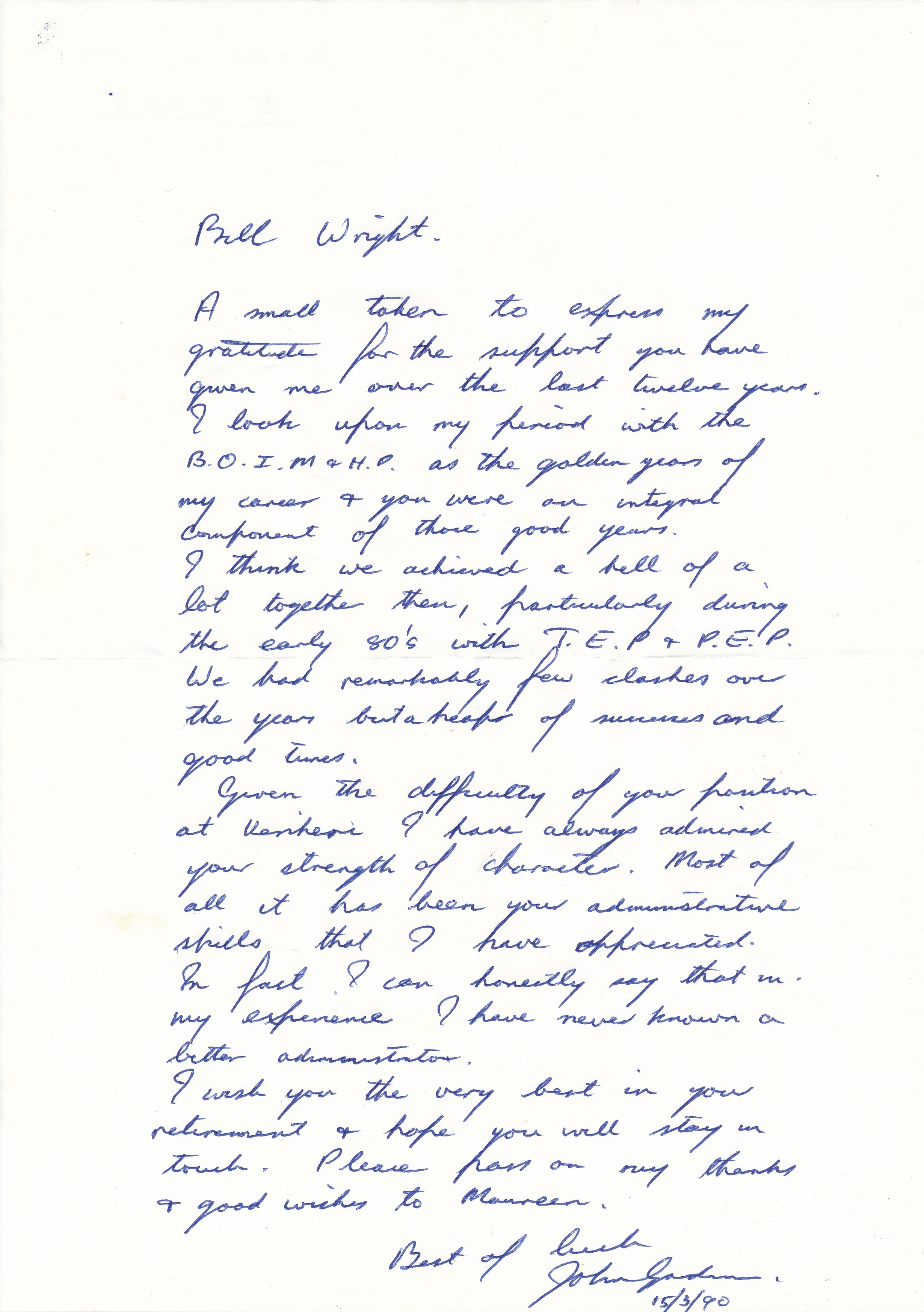

The Last Word from the Chief Ranger:

NB: The note was accompanied by a bottle of Whisky.